|

| Inchcolm war defense |

|

| Inchcolm island |

|

| Firth of Forth |

time. At the western end of the Forth was Stirling, the pivotal location for many of

Scotland’s invasions from Bruce’s time to the Jacobites. Heading eastwards was

Rosyth, in 1914 the home of the Royal Navy’s Battle Cruiser Squadrons. Then it was

the Forth Rail Bridge, an important link between the south and north of Scotland

during wartime. Further east again sits Scotland’s capital Edinburgh and along both

shores many ports and harbours essential to Scotland’s mercantile trade and the

fishing industry.

Since the late nineteenth century fortifications had been erected on the islands in

the Firth of Forth and shore batteries had been built along the Lothian and Fife

coasts.

Key to the defences was the island of Inchkeith which dominated the Forth, but gun

emplacements were also placed on the Forth islands of Cramond, Inchmickery,

Inchcolm and Inchgarvie. There were also emplacements at North and South

Queensferry

By 1914 the defences had evolved into three concentric lines of defence. The inner

one at the Forth Rail Bridge to protect Rosyth had defences at Carlingnose at North

Queensferry, Inchgarvie Island under the bridge itself, and more emplacements at

Dalmeny.

The next line of defence was Dalgety‐Inchcolm‐Inchmickery‐Cramond.

The outermost defences were centred on Inchkeith Island and there were linked

batteries at Leith and Kinghorn.

Each of these defensive rings were linked by telephone and telegraph so any

invaders who got past the first line of guns still had two more lines to breach before

they could get through to the bridge and Rosyth.

The men who manned these guns in wartime were Territorials of the Royal Garrison

Artillery. Their HQ was Leith Fort, which was also the Headquarters of the Royal

Artillery in Scotland. The Forth Royal Garrison Artillery had four batteries based in

Edinburgh and two more in Fife who drilled on the mainland and trained for war on

the islands.

Also on the islands were Royal Engineers who updated and maintained the defences.

A visible record still survives to this day of one of the units who served on Inchcolm.

576 (Cornwall) Works Company, Royal Engineers recorded that the tunnel built in

1916‐17 on the east part of the island was their work.

To back up the guns, Territorial Force infantry, cavalry and artillery brigades manned

the coasts from Dunbar to Stirling and back up to the Tay. In August, 1914 the

1 Territorial units of Edinburgh were all sent to war stations along the Lothian coast

either as part of the Forth Defences or the Lowland Division.

Up until 1916 it was expected that any attack on the Forth would come from the sea

and the defences all pointed seawards. On 2 April, 1916 the Germans launched a

Zeppelin raid on Rosyth. Unfortunately they mistook Leith for Rosyth and bombed

the city and port instead of the naval dockyard.

From October, 1916, 77 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps patrolled the Lothians

and the Forth to see off any more Zeppelins. They joined the Royal Navy Air Service

aeroplanes flying from East Fortune.

As part of the Forth defences the Royal Navy also employed airships to see far out

into the North Sea. At first they used the non‐rigid blimps which would sit high above

the Forth but by 1918 they were using rigid airships to patrol far out into the North

Sea looking for German ships.

A German U‐Boat, U‐21 nearly got to Rosyth in 1914 but that was the only one. The

Zeppelins only made one raid. It had been a long and sometimes lonely existence for

the gun crews on the Forth’s islands but at the end of the war they could look back

with some pride that their defences had held firm.

http://www.edinburghs-war.ed.ac.uk/home_front/documents/PDF_forth_defences_and_zeppelin_raids.pdf

Atlantis articlehttp://atlantisrisingmagazine.com/2009/07/01/the-pyramids-of-scotland-revisited/

The Pyramids of Scotland

(Originally published simultaneously in Atlantis Rising #35 — September/October, 2002 — and Duat CD-Magazine #1)

Egyptian tycoon Mohamed al Fayed, owner of Harrods and father to Dodi, Princess Diana’s companion in their fatal 1997 car crash, has listed his ten favorite books on the Manchester Guardian’s website. One of them is “The Scotichronicon: A History Book for Scots,” described simply as “Scotland’s debt to Egypt revealed at last.”

What does he mean?

Completed in the 15th century by Walter Bower, Abbot of Inchcolm, the Scotichronichon begins with “The Legend of Scota and Gaythelos.”

The legend claims that Scota was daughter to the pharaoh who pursued the Children of Israel out of Egypt on their Exodus to the Promised Land. Gaythelos, an exiled prince of Greece, was Scota’s husband. Shortly thereafter, the couple is forced to lead an Exodus of their own out of Egypt—going first to Spain, then Ireland and, finally, to Scotland, which was named after Scota. Their bloodline flowed down the centuries through all the high kings of Ireland and Scotland. But Gaythelos’ pedigree was more ancient still—stretching back many more generations to Old-Testament patriarch Noah, eldest survivor of the Biblical Flood.

While historians argue that it was politically useful for royal families to invent fanciful lineages of great antiquity, could it be that the legend is more fact than fancy?

On March 27, 2000, I received the following comment from an eminent UK archaeologist regarding my report about an intriguing Scottish leyline configuration I’d discovered:

“I do understand your quest for knowledge,” she said, “but please, please beware of the whole leyline question. It is so easy to draw lines and make assumptions, from prehistory onwards, but that way madness lies.”

Hmmm…!

For those unfamiliar with the term, leylines are the curiously exact alignment of ancient archaeological sites, conjoined over many miles, that academics dismiss as mere coincidence and that those who discover them cannot explain the “why” of. Crossing mountains and large bodies of water as they do, leylines never seem to follow the easily trod path—only the straight one.

So what use were they?

I was studying the Knights Templar at the time—that enigmatic order of warrior monks barbarously suppressed in France during the early 1300s for believing in things that contradicted Vatican dogma at a most inconvenient time.

My discovery was as follows:

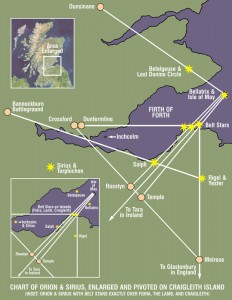

I had noticed a geometrical connection between two pre-eminent Templar sites in Scotland—their earliest-known headquarters in the tiny village of Temple and that famed architectural repository of Templar and Freemasonic lore, Rosslyn Chapel. Each could be connected to a third by straight lines drawn through two small islands to the northeast in the Firth of Forth—the islands of Craigleith and Fidra. Each connected to the Isle of May, 20 miles further out, where one tradition tells us the Templar fleet landed after escaping from France. Historian Stuart McHardy has recently suggested that “the May,” as it’s locally known, is in fact the Isle of Avalon where legendary King Arthur is buried. Glastonbury supporters, staunchly supportive of their own pet site’s long-held Avalonian connections, are not impressed.

I had noticed a geometrical connection between two pre-eminent Templar sites in Scotland—their earliest-known headquarters in the tiny village of Temple and that famed architectural repository of Templar and Freemasonic lore, Rosslyn Chapel. Each could be connected to a third by straight lines drawn through two small islands to the northeast in the Firth of Forth—the islands of Craigleith and Fidra. Each connected to the Isle of May, 20 miles further out, where one tradition tells us the Templar fleet landed after escaping from France. Historian Stuart McHardy has recently suggested that “the May,” as it’s locally known, is in fact the Isle of Avalon where legendary King Arthur is buried. Glastonbury supporters, staunchly supportive of their own pet site’s long-held Avalonian connections, are not impressed.

Exactly midway between Craigleith and Fidra was a tiny island known locally as “the Lamb,” which would enter the equation later.

I had then drawn three additional interconnected lines.

The first stretched exactly due south from Craigleith to the Cistercian Abbey of Melrose. Founded contemporaneously by Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, the Cistercians and the Templars are thought by many to be two arms of a single order. Interestingly, I later discovered that if the line is continued far to the south of Melrose it arrives, unerringly, at Glastonbury.

The second line headed in a northwesterly direction from Melrose, exactly through both Temple and Rosslyn, to a place called Crossford, where it intersected the third line.

That third line headed due west from Craigleith, passing through Dunfermline Abbey along the way. Robert the Bruce, quasi-hero of my “Mystery of Bannockburn” article (AR#31), was buried at Dunfermline, but his heart was removed and carried on an ill-fated journey to the Holy Land. Brought back to Scotland from Spain, which is as far as it got before the “infidel” horde put a stop to its passage, the heart was interred at Melrose, just a day’s ride shy of a reunification with Bruce’s body. History does not tell us why.

In effect, I had found a compass and a square connecting several Templar and Freemasonic sites in southern Scotland. And as many of you will know, the compass and the square are important symbols of Freemasonry. They can be seen on every Freemasonic lodge in the world—surrounding the mysterious letter “G,” which has been variously interpreted as God, Gnosis, or Geometry.

My leyline configuration buzzed with a significance that seemed to preclude mere coincidence. But a cautionary finger had been raised on my leyline investigation, so I put it on the back burner—but not for long.

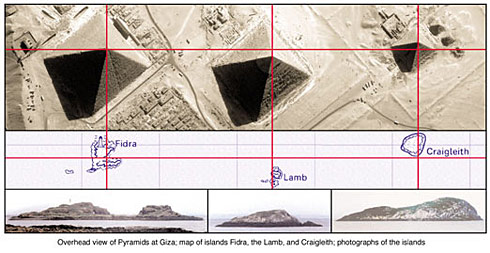

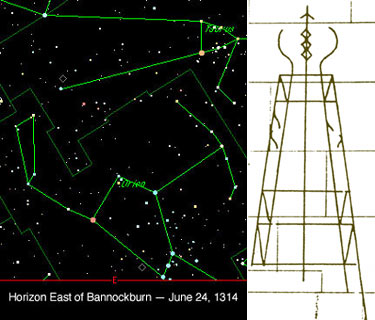

While researching my Bannockburn piece, I often viewed a computer simulation of the eastern sky as it would have appeared on the day of battle. Countless times I observed the three equidistant “belt stars” of the constellation Orion rise invisibly in the daylight sky, and at some point I noticed they were rising over Fidra, the Lamb, and Craigleith. Throwing caution to the wind, I decided that the Lamb deserved some attention—sanity be damned.

I then drew a line from the May, through the Lamb and the exact midpoint between Rosslyn and Temple, just to see where it might lead. It led to a tiny spot called Tara, far away in Ireland, where the high kings of that land were crowned—kings descended from Scota and Gaythelos.

Curiouser and curiouser!

On a wall of Rosslyn Chapel’s underground crypt, the oldest and holiest structure in the building, is what’s been called a “working Masonic drawing.” It is shaped more like an obelisk than a pyramid, and yet it sang a siren song to me. The central line of the drawing passes through three pyramids—as viewed from above!

Why despoil a holy place, forever, with a drawing that could have been more easily scratched in dirt? Is that not curiouser still?

When it is visible, Orion is the most spectacular constellation in the sky—and little wonder. Of all the constellations, Orion is the least abstract—and is strikingly humanoid in shape. But of all its seven main stars, the belt stars have received the lion’s share of attention over the millennia. Called simply “three in a row” by native North Americans, their relative positions have been recently correlated, by researcher Robert Bauval, to the groundplan of the pyramid complex at Giza.

Orion and nearby Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, are inextricably linked to both the ancient Egyptian belief system and the mysterious symbolism inherent in today’s bizarre Freemasonic rituals, practiced since the brotherhood’s earliest days, but now little understood—even by Freemasons, themselves.

Could the key to what has long been referred to as “The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry” have been hidden in the light of day, east-southeast of Bannockburn, on June 24, 1314?

On a wild hunch, I decided to bring Orion and Sirius down to Earth, laying the three belt stars exactly on top of the three islands in the Firth of Forth. Incredibly, Sirius lay on tiny Inchcolm island, farther west in the Forth, where Walter Bower had written his Scotichronichon. In Richard Hinckley Allen’s “Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning,” the author cites a Hindu astrological tradition which personifies Sirius as a hunter who shoots a three-jointed arrow which pierces Orion through the waist.

It’s interesting that Walter Bower’s surname derives from the craft of bowmaking? Could it be that Bower, finishing his book, let fly an arrow of forbidden knowledge towards a more enlightened future?

The other stars in the Orion/Sirius configuration, however, were not so accommodating. Bellatrix, the star that marks Orion’s right shoulder, lay insignificantly in the sea, far from the May, the island my “compass” had suggested played a major role in what looked increasingly like a message from the past.

On another wild hunch I enlarged the stellar group, pivoting it on Craigleith, until Bellatrix lay on the May.

The result was riveting!

Sirius now lay on Torphichen, headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller—the Catholic military order that “absorbed” the remnants of the outlawed Templars and, by the grace of Rome, acquired most of their property to boot. Recent research, however, suggests the Templars may have continued to maintain a secret autonomy within the Hospitallers.

But that’s just the beginning.

A line drawn from Bellatrix through Orion’s left shoulder (Betelgeuse), led directly to Dunsinane Castle, immortalized in Shakespeare’s “Macbeth.”

Keith Laidler, author of “The Head of God,” relates an interesting tale about Dunsinane. He cites an 1809 newspaper article reporting that a large stone of “the meteoric or semi-metallic kind” had been discovered hidden beneath the castle. The stone was sent to London for study, but disappeared en route. Laidler goes on to say that it was Scotland’s real Stone of Destiny, and that the stone upon which British monarchs have since been crowned is a substitute. This real stone, he claims, is the Throne of Akhenaten, the heretic pharaoh who tried and failed to establish monotheism in Egypt shortly before the Biblical Exodus. That stone began its journey to Scotland with Scota, who Laidler says was Akhenaten’s daughter, while Akhenaten led the Exodus to the Promised Land under the name given to him in the Bible—Moses!

Could today’s Christians and Jews be linked to a common Egyptian patriarch? The implications are staggering!

But where did Betelgeuse lie—the star between the May and Dunsinane?

My map showed a featureless landscape. But subsequent research revealed that an ancient stone circle, now “lost,” had once existed to the west of the nearby hamlet of Dunino. If the lost circle proves to lie under Betelgeuse, archaeologists will have a merry time losing it again.

The stars at Orion’s feet also lay in interesting locations.

Rigel, Orion’s right foot, stood on the lands of Yester. Built in 1297 by the “Wizard of Yester,” Hugo de Gifford, Yester Castle stands over a sizable underground cavern known as the “Goblin Hall,” where Hugo practiced his “magic,” and passed to the Hay family in the 14th century. Father Richard Hay later wrote a history of the Sinclairs of Rosslyn. Lord William Sinclair, it’s said, actually moved his castle to free up the chapel’s building site. Location was everything, I guess—even back then!

Saiph, Orion’s left foot, stood between the towns of Musselburgh and Prestonpans, on land once owned by the Cistercian monks of Newbattle, and later associated with the Templar-connected families of Seton and Kerr. Besides hosting one of Scotland’s first Masonic Lodges, the area also hosted the first meeting of the North Berwick Witches—accused in 1590 of plotting to murder Scotland’s first officially Masonic king by the “abomynable cryme of wytchcraft.” The trumped-up case helped kick off over 100 years of witch persecution in Scotland, barely covered in mainstream histories.

Here’s the kicker:

A line drawn from Rigel, through Saiph, led directly to Bannockburn, site of the great Scottish battle for independence where, on Midsummer’s Day, 1314, a great message was hung invisibly in the dawn—a message meant to eventually reveal that we’ve been fooled for a very long time.

A line drawn from Rigel, through Saiph, led directly to Bannockburn, site of the great Scottish battle for independence where, on Midsummer’s Day, 1314, a great message was hung invisibly in the dawn—a message meant to eventually reveal that we’ve been fooled for a very long time.

Surprise, surprise!

Last April I drove out of Edinburgh to take photographs of the three belt-star islands, and was struck by the shape of North Berwick Law, the peak that stands just to the south of Craigleith. It looked remarkably like a pyramid, so I made some calculations.

According to Hancock & Bauval’s “Message of the Sphinx,” the bottom of the square pit in the center of the Great Pyramid’s subterranean chamber lies 610 feet below the pyramid’s summit platform. North Berwick Law stands at 613 feet!

Care to split some very fine hairs, anyone?

From the top of North Berwick Law the islands of Craigleith, the Lamb, and Fidra lie stretched along the coast like pearls on a string. The questions cannot be avoided: How could they possibly be positioned, each to the other, like the Giza pyramids? How could they lie below the rising of Orion’s belt in the Bannockburn dawn? How could North Berwick Law be pyramidal? How could natural geological features be so conveniently where they are in the first place without divine intervention? And why, in that small corner of the world, do the voices of myth and history join to sing a siren song to people like me, and maybe you?

Perhaps I can suggest answers to some of those questions, and raise new ones.

Risking the hoots and hollers of academia, I propose that North Berwick Law and the islands of the Forth are where they are due to large-scale “terraforming”—i.e. shaping the landscape to suit a purpose that is only now emerging from the mists of time.

Risking the hoots and hollers of academia, I propose that North Berwick Law and the islands of the Forth are where they are due to large-scale “terraforming”—i.e. shaping the landscape to suit a purpose that is only now emerging from the mists of time.

On a mid-17th-century map of the area, supposedly based on the original but now mysteriously lost drawings of late-16th-century mapmaker Timothy Pont, the three belt-star islands are shown. But there are curiosities about their presentation. The orientation of the grouping is wrong, and the Lamb is called “Long Bellenden.” The name is especially curious because the Lamb is not long at all. In fact, it is the shortest of the three islands. Could it have been shortened to “sharpen” the aim over the vast distance from the May to Tara? Might not the islands have been one long island at some point, carved from the mainland by a cataclysm the ancient “mythmakers” would only hint at, and then cut into three? And might not North Berwick Law have been “shaped” from the tailings of such an enormous excavation? Just take a look at Fidra, sliced almost in two and bored clear through, and ask yourself if it was shaped by God, Nature, or the helping hand of man!

I realize I stand on shaky ground here, but not without consideration—and I welcome your arguments. Be warned, however, that this article could have been a lot longer. The simple grid shown here has blossomed into greater bloom—and I’m loaded for bear!

History tells us we’re the greatest civilization ever to walk the face of the earth. Wars have been fought since time immemorial over matters of faith—each side believing that God is on their side. But what if the things that make us swing our swaggersticks are wrong? Who’ll forgive us for the damage we’ve done, fool unto fool, believing in lies?

Orion was brought down to earth in Scotland, and then later nailed in place by tales of a legendary stone, a holy chalice, a magical sword, a battle the world would not soon forget, and a once-and-future king named Arthur.

Much care was taken, over dangerous times, to make us think. Perhaps now, more than ever, it’s time we did.

No comments:

Post a Comment